The Basics#

Machine learning#

Machine learning is about making models out of data. One of these model-building tasks we will see in this class is regression. In regression, you are given, for example, the characteristics of a house, and you have to predict its price. You gather some data on house characteristics and the corresponding prices. You make a mathematical model that connects the characteristics to the prices, and, finally, you fit the model’s parameters by minimizing the prediction error. Now if someone gives you a new set of building characteristics, you can predict the price.

Causality#

In simple regression, nothing special distinguishes the price from the house characteristics. You can also make a model that tells you the house’s characteristics from the price. But there is a big difference between the former model and this one. The first model (house characteristics to price) is a causal model; it follows the causal mechanisms (better materials, better design, more rooms, etc., cost more). The second model (price to house characteristics) captures statistical correlation. You cannot renovate your house simply by increasing its price! You cannot even intervene to increase its price. It is not sufficient to ask for a higher price. There must be someone who wants to pay for it!

Without causality, machine learning is useless. We must always strive to make our models causal. A causal model is a model that attempts to capture the mechanisms that govern a given phenomenon. We will use the language of structural causal models (SCM), developed by the computer scientist Judea Pearl, to formalize the concept. A structural causal model is a collection of two things:

A set of variables. These are variables that our model is trying to explain (endogenous), but also other variables that may just be needed (exogenous).

A set of functions that give values to each variable based on all other variables.

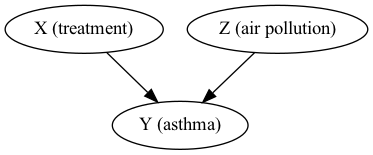

Example: Asthma model (J. Pearl)#

Suppose we are trying to study the causal relationships between a treatment \(X\) and lung function \(Y\) for asthmatic individuals. However, it is plausible that \(Y\) also depends on the air pollution levels \(Z\). The final ingredient is the function that connects \(X\) and \(Z\) to \(Y\):

Graphical representation of causal models#

Every SCM corresponds to a graphical causal model. These are directed acyclic graphs (DAGs). You can read them off the SCM form. All variables become nodes, and you add arrows from the input variables to the function output. Let’s look at an example.

Example: Asthma model - Graphical causal model#

Here I am representing each variable with a node. The node at the beginning of an arrow is the direct cause of the node at the end.

Fig. 1 An example of a causal graph.#

Predictive Modeling#

What if we have an excellent, causal model, but it requires inputs that are unknown or random? Then, it is impossible to be certain about the model predictions. Predictive modeling is all about dealing with such uncertainties.

Some examples of uncertain model inputs are:

the value of a model parameter,

the initial conditions of ordinary differential equations,

the boundary conditions of a partial differential equation,

the value of an experimental measurement we are about to perform, and even

the mathematical form of a model.

There are two kinds of uncertainties. If something is truly random, we say it corresponds to aleatory uncertainty. If something is unknown, we say it corresponds to epistemic uncertainty. In other words:

Aleatory uncertainty is associated with inherent randomness.

Epistemic uncertainty is related to a lack of knowledge.

You can reduce epistemic uncertainty by collecting more data, improving measurement instruments, and doing more analysis. You cannot reduce aleatory uncertainty. There is a long philosophical debate about the distinction between aleatory and epistemic uncertainties. Sometimes, deciding if you have one kind or the other is hard. But we do not care. In this class, we will argue that probability theory is sufficient to describe both uncertainties. So, to make predictive models, we will need to formulate our models in a probabilistic way.

Scientific Machine Learning#

Scientific machine learning is machine learning for scientific and engineering applications. Of course, models have to be causal. Typically, scientific and engineering problems have quite a bit of uncertainty. So, ideally, we want to wrap things in a probabilistic framework and make predictive models.

Finally, when dealing with scientific and engineering problems, we know quite a few things on top of the data. For example, the temperature satisfies a differential equation; the mass is conserved, and so on. If we use this physical information, we can make models that can extrapolate beyond the data we have seen. If we use such information, we are doing physics-informed machine learning.